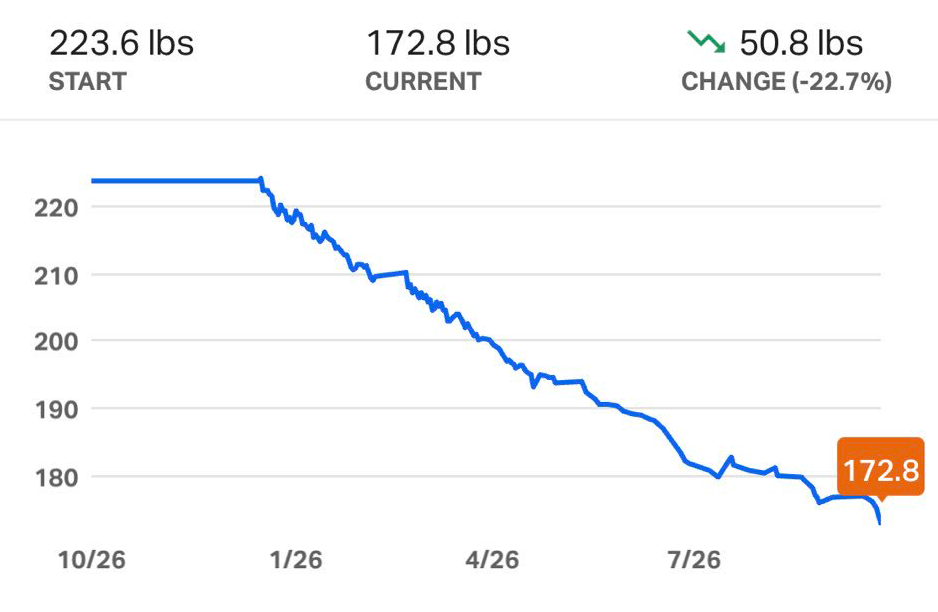

On January 10, 2019, I weighed in at 223 lbs. On October 20, I weighed in at 173 lbs. That’s 50 pounds lost (22.7 kg) in 10 months.

In this blog post, I’ll share a few thoughts and lessons from this experience:

- Looks can be deceiving

- Weight loss is a long game

- Maintaining muscle mass is hard

- Losing weight is just the beginning

1. Looks can be deceiving

I decided to lose weight earlier this year when I weighed myself and found that I was over 220 lbs. At 5’11” (~1.8m), 220 lbs (~100 kg) is a lot of weight to be carrying around, and it neither looked great, nor felt great: in fact, over the previous year, I had gone through several minor injuries, especially from running (e.g., calf strains, knee pain), and my guess was that most of them were due to lugging around lots of extra body weight.

All that said, I hadn’t planned on losing 50 lbs; honestly, I didn’t think I had that much to lose! The original plan was to drop down to around 190 lbs, but when I got there, it was clear that I was still carrying around a lot of extra weight, so I just kept going. I got to 173 lbs before I decided I was at a point where my body weight looked “normal.”

As it turns out, looks can be deceiving. Here’s what I looked like back in October, 2018, a few months before starting my weight loss, at a body weight of around 215 - 220 lbs:

![]()

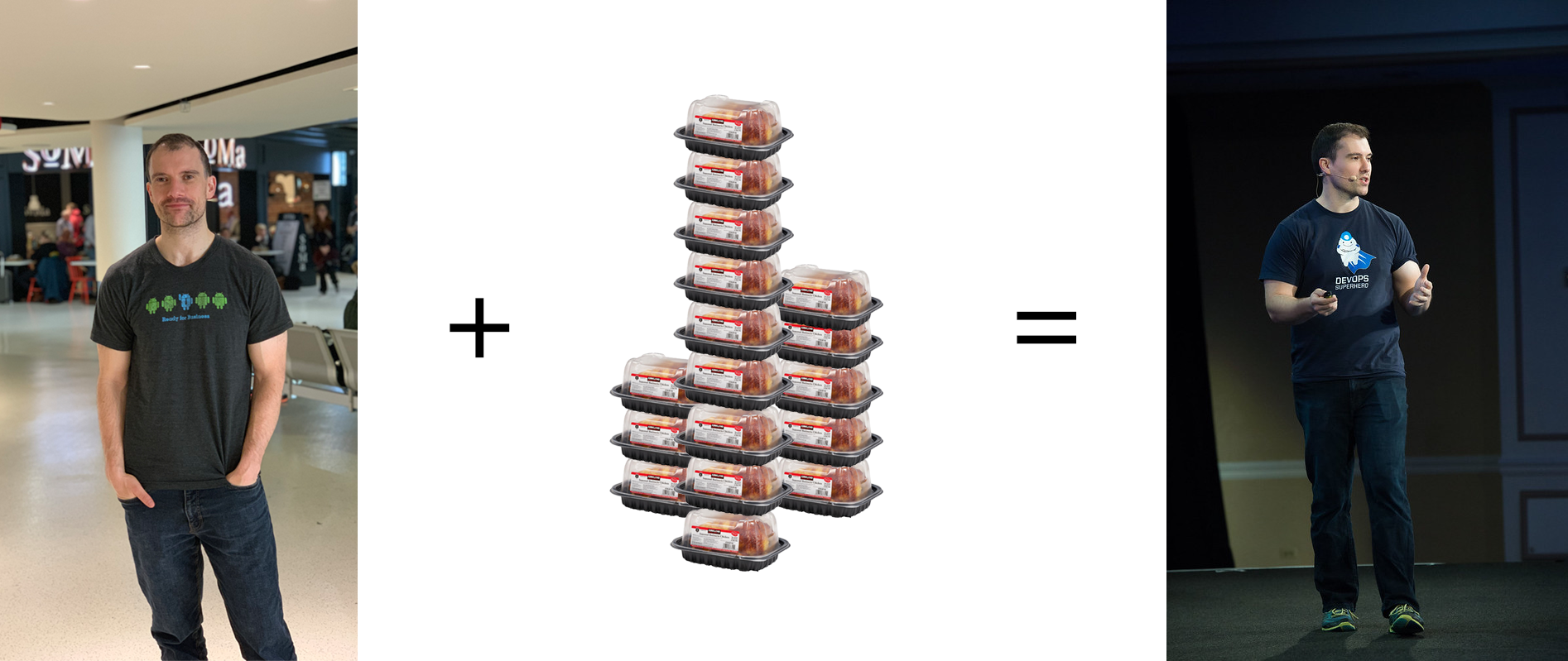

And here’s me about a year later at 173 lbs:

I mean, sure, you can tell I’ve lost some weight, but 50 pounds? Shouldn’t that be a bit more noticeable? To put it into perspective, consider the rotisserie chicken from Costco:

Those weigh about 3 pounds each. That means that I was carrying around the equivalent of 17 rotisserie chickens in extra body weight:

I just imagine trying to walk around with 17 of those things tucked under my shirt… and I can’t quite make it work in my head. This experience made me realize that I have no idea what my “normal” body weight should be, and going based on appearances is not an effective way to figure it out.

I’ve been on the heavy side my entire life, so I guess my perception of “normal” is completely skewed. Before I started this whole process, I would’ve thought I’d be too skinny at 173 lbs, but even at this weight, I’m still a very long way from “skinny” (which isn’t the goal anyway). That means that my entire life, I’ve been carrying around 50+ pounds of extra weight: every time I went on a run, got up off the couch, or walked up a flight of stairs, I was lugging around 17+ extra rotisserie chickens, placing extra stress on my heart and damaging my health, for no reason whatsoever.

Those ideal height/weight charts you saw in school aren’t perfect, but they are likely a reasonable starting point, and for my age, gender, and height, this calculator shows that my ideal weight should be around 158 - 171 lbs. So even after losing 50 lbs, I’m still heavier than I should be, and have a bit more work to do!

2: Weight loss is a long game

Your body requires energy for all your basic functions: walking, thinking, breathing, and everything else you do requires some amount of energy that can be measured in calories. The 1st law of thermodynamics says energy can neither be created nor destroyed, so if you:

- Eat more calories than you burn (calories in > calories out), your body stores the excess as muscle or fat, and you gain weight.

- Burn more calories than you eat (calories in < calories out), your body makes up the deficit by burning muscle or fat for energy, and you lose weight.

Of course, real-world biology is a bit more complicated than this, including the effect of genetics, hormones, and the types of food you eat (see, Some food for thought for more details), but at a macro level, calories in < calories out is still the most effective model I’ve found for weight loss.

To make use of this model, you’ll need to:

-

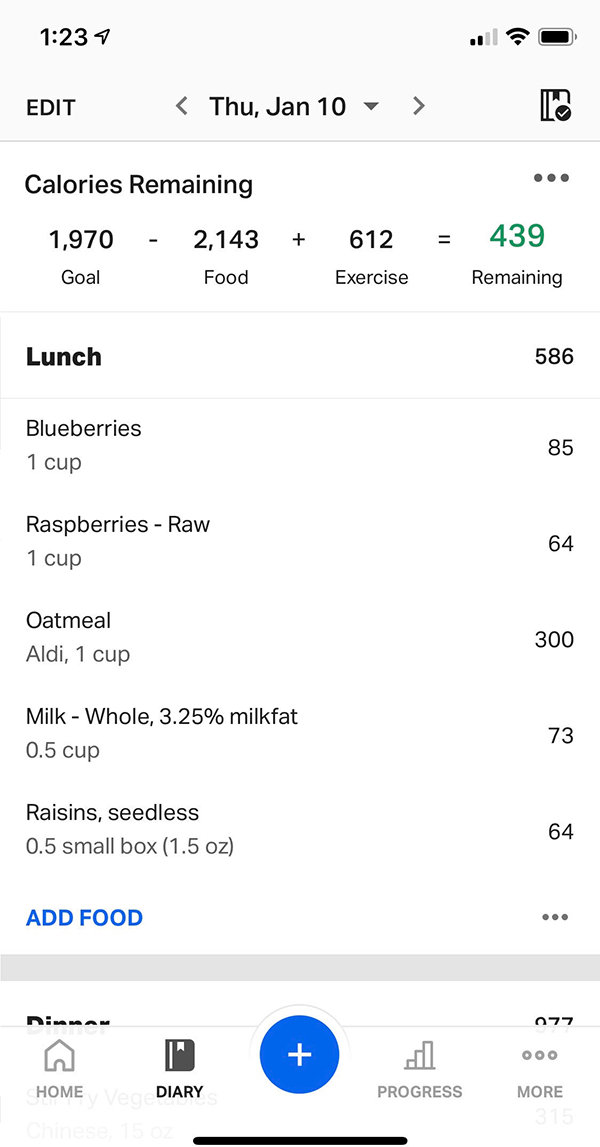

Track your calories: Every single day, you’ll need to calculate how many calories you take in (i.e., by eating) and how many calories you burn (i.e., via exercise), and make sure you’re in a caloric deficit, eating fewer calories than you’re burning. It’s a bit tedious to do all this tracking, but fortunately, there are many websites and mobile apps that make it easier. I use MyFitnessPal, a free mobile app with a huge built-in database that includes calorie counts and other nutrition facts for thousands of foods and calorie burn estimates for hundreds of activities.

-

Track your weight: No matter how carefully you track calories, your numbers will be inaccurate. You’ll overestimate some things and underestimate others; two seemingly identical foods will turn out to have wildly different calorie counts (e.g., a dish you make at home versus the “same” dish at a restaurant); the way you process calories depends on the food; and so on. That’s OK: your goal is not to publish a scientific paper with perfectly accurate calorie counts, but to get into a caloric deficit so you lose weight. So how do you know you’re in a caloric deficit? Use a scale! Weigh yourself every few days and keep adjusting your diet, exercise, and calorie estimates until you’re losing weight at the rate you expect.

This brings up an important question: what rate of weight loss should you be aiming for? To answer that, let’s look at the math:

- One pound of fat contains roughly 3,500 calories.

- The typical person burns roughly 2,000 calories per day depending on your activity levels, body weight, and genetics.

So, even if you ate nothing at all for an entire day, you’d still lose less than 1 pound of fat. Of course, you’ll have to eat something, so it’s a question of how much of a calorie deficit to aim for. Too big of a calorie deficit is unhealthy and unsustainable, as you’ll be constantly be hungry and tired; too small of a calorie deficit means the weight loss will take forever. The sweet spot for most people is a deficit of around 250 - 750 calories per day, which works out to 0.5 - 1.5 lbs of weight loss per week. For example, if you calculate that you burn 2,000 calories per day, then if you eat around 1,500 calories per day, you’ll lose about 1 pound per week.

At 1 pound per week, if you want to lose 25 pounds, that’s roughly 6 straight months of weight loss; if you want to lose 50 pounds, you’ll be at it for around a year. That means that every single day, multiple times per day, you’ll have to think about what to eat, how much to eat, how often to eat, what exercise to do, and so on—for months on end. That’s a long time. Far longer than most people have in mind when they think about weight loss.

To succeed at such a long-term endevour, you’ll have to take into account not only calories, but also your unique psychology physiology, preferences, genetics, lifestyle, and so on. You’ll need to do lots of experiments to figure out which low calorie meals you find tasty (if you hate what you’re eating, you won’t be able to stick with it for the long term), which foods you find filling versus which ones seem to make you hungrier (if you’re always hungry, you won’t be able to stick to your diet for the long term), and how to arrange your life to make dieting easier, such as eating out less often, eating from smaller plates, not drinking your calories, and not keeping sweets or other temptations in the house (if your diet relies on constant superhuman willpower, you won’t be able to stick with it for the long term). When it comes to weight loss, you have to play the long game.

3. Maintaining muscle mass is hard

For most people, the goal isn’t to lose weight, but to lose fat. Unfortunately, when you’re in a calorie deficit, your body may make up the deficit by burning not only fat, but also muscle mass. Losing muscle mass is not desirable in terms of health, fitness, or appearance, so it’s critical to give your body plenty of reason to burn primarily fat and retain (or perhaps even increase) muscle mass. The two most effective ways I’ve found for doing that are:

-

Strength training: the best way to convince your body to maintain or grow muscle mass is to lift heavy things. And I do mean heavy: think full-body exercises (e.g., squat, deadlift, press) done with heavy weights for low reps. The gold standard is the routine detailed in Starting Strength (see Light reading for heavy lifting for more info).

-

Protein: eating plenty of protein is also important for maintaining muscle mass. I’d typically aim for 0.5 - 0.75 grams of protein per pound of body weight (so around 80 - 150 grams of protein per day). To stay within your calorie goals, you’ll need to look for foods that have lots of protein with relatively few calories: check out this handy protein per calorie spreadsheet for a nice guide to “lean” foods. Note that this guide is just a starting point: e.g., some of my favorite items—cottage cheese and oatmeal—are missing from this list, so make a copy of the spreadsheet and add your favorite foods to it to see where they rank.

So, how did I do in terms of maintaining muscle mass? Well, I didn’t measure body fat or lean body mass (e.g., via hydrostatic weighing), so I don’t have an exact answer. The best I have is a measure of my numbers at the gym. These days, I’m not training nearly as hard as I used to, but I still do a combination of strength training (e.g., squat, deadlift, press) 1-2 times per week and conditioning (e.g., running, rowing, boxing) 1-2 times per week. Here are the results from the last 10 months:

| Jan, 2019 | Oct, 2019 | |

|---|---|---|

| Body weight | 223 lbs | 173 lbs |

| Squat | 365 lbs (1.64x BW) | 360 lbs (2.08x BW) |

| Deadlift | 425 lbs (1.91x BW) | 405 lbs (2.34x BW) |

| Bench press | 295 lbs (1.32x BW) | - |

| Overhead press | 185 lbs (0.83x BW) | 170 lbs (0.98x BW) |

| 5k run (treadmill) | 19:55 | 18:56 |

| 5k row (C2 rower) | 19:58 | 19:17 |

(Bench press numbers not included for October, 2019 due to a rotator cuff injury that has prevented me from doing the exercise the last few months.)

Overall, my strength numbers went down 2-8%. What’s interesting is how the numbers decreased. When I was lifting consistently, my numbers were actually increasing, albeit very slowly. However, whenever I took a trip somewhere for work or vacation and missed a week or two of exercise, I’d come back to find my lifts were down ~10 pounds, and getting those numbers back up while losing weight proved to be very difficult. It could take an entire month to recover just 5 pounds on a lift, only to have another trip come up, which would drop my lifts back down again by 5-10 more pounds. Over 10 months of this, I unfortunately ended up in the net negative.

So, overall, I likely lost a little bit of muscle mass. Being inconsistent with workouts is always a bad idea, but when you’re losing weight, it’s especially punishing. Fortunately, a 2-8% drop isn’t that major, especially compared to the fact that my bodyweight dropped ~22%! Relative to my new body weight, my lifts actually look far better, and my Wilks score is significantly higher. Moreover, my conditioning numbers have improved too. Running in particular has gotten much easier. With relatively little effort, I was able to shave almost a full minute off my 5K time. Also: no more knee pain or calf issues. It turns out that carrying an extra 50 lbs with each step makes a big difference!

4. Losing weight is just the beginning

Sadly, this is not my first time losing weight. Over the last 15 years or so, I’ve lost weight twice before, getting down to the 180 - 190 lbs range… But then, slowly, over the subsequent 5-10 years, I eventually gained the weight back and ended up over 220 lbs again. The 173 lbs I got down to this time is the lowest I’ve ever been, but even getting to this milestone is still just the beginning. The real test will be figuring out how to stay at this body weight for the long term.

Weight gain is insidious. It’s often portrayed as the result of laziness, sloth, and stupidity, but as someone who has struggled with body weight my entire life, I think this is the wrong narrative. I’ve lived an active lifestyle the last 15 years, doing 4-6 intense workouts per week (both strength and conditioning), walking around an hour every day (I haven’t even owned a car the last ~5 years), and eating a healthy diet (no sweets, no snack food, no highly processed food, minimal restaurant food, etc).

Despite all that, the truth is simple and depressing: if I don’t obsessively watch my diet every single day, I will be overweight.

It shouldn’t be this way. I’m young, healthy, with an active lifestyle, and well-read on diet and exercise. It shouldn’t be this hard for me to not get fat. And given that about 70% of Americans are overweight or obese, I know I’m not the only one struggling.

It wasn’t this way for most of human history. In fact, it wasn’t even this way just 50 years ago! Starting in the late 70’s and early 80’s, obesity rates begin to rise sharply. That’s not nearly enough time for our genetics to change in any significant way, and there’s no reason to assume that we all suddenly got lazy, slothful, and stupid at the same time. So what about lifestyle changes? Don’t we eat more, do less manual labor, and less exercise nowadays? Nope, nope, and nope again. It turns out that the average person ate more calories per day in the 70’s than today, you’re more likely to be obese if you are in a manual labor profession, and we exercise about the same nowadays as back in the 70’s (source).

We don’t know all the answers of what’s causing the obesity epidemic, but I can’t help but think that a huge part of it is that our food supply is broken. Some combination of overly processed foods, antibiotics, pesticides, growth hormones, and other factory farming practices has made it far more difficult to maintain a healthy body weight in the modern era than it ever was before. It’s not that we’re lazy, slothful, and stupid—it’s that we’re being poisoned by our own food system.

I don’t have a good solution for this. Ignoring it isn’t an option: just because a problem isn’t your fault doesn’t mean it’s not your responsibility to deal with it. We’re all going to have to work harder than past generations to stay healthy. That means losing 50 pounds was the easy part—it’s staying at that weight that’s the real challenge. And it’s a challenge I’ll be dealing with the rest of my life.

If you’re in the same boat, I hope you’ve found this blog post helpful, and I’d love to hear what has and hasn’t worked for you in the comments.

Yevgeniy Brikman

If you enjoyed this post, you may also like my books, Hello, Startup and Terraform: Up & Running. If you need help with DevOps or infrastructure, reach out to me at Gruntwork.