The other day, I was chatting with a LinkedIn product manager about a new app he is working on and I posed a “hard” question: what incentive would users have to use the app initially and on an on-going basis? Before the product manager had a chance to answer, someone nearby chirped in: “you should put in some game mechanics!” Sigh. This is not the first time I’ve heard this. “Game mechanics” have been all the rage the last few years. Everywhere you look - from foursquare, to yelp to Xbox - you can find badges, leader boards and reward systems. And while it is sometimes effective, most implementations are either totally useless, or worse yet, counterproductive.

In fact, the very idea that cramming “game-like” elements into a product is enough to attract users is misguided; the proposal of using “game mechanics” as the primary way to drive and maintain user engagement is a short road to failure. I think these misconceptions come from a lack of understanding of two key concepts:

- Gameplay psychology

- The role of game mechanics

Gameplay psychology

The first reason that game mechanics probably won’t work for you is that you don’t understand game mechanics. Before you go off and add a leader-board or badging system to your next product, please take the time to go through Sebastian Deterding’s superb presentation “Pawned. Gamification and its discontents”. I’m embedding it within this blog post as the presentation beautifully covers the many mistakes and misconceptions about what gameplay is really all about:

One of the key takeaways from this presentation is that most people don’t understand motivation. Think of the most common game mechanics you see in most products today: badges, scores, and progress bars. foursquare has it, so it must work, right? Wrong. These “external rewards” are rarely effective because gamers and humans in general are typically not motivated by external factors, but rather by intrinsic ones. In fact, studies have shown that external rewards and pressures can often act as de-motivators. If you’re not convinced, it would be well worth your time to watch Dan Pink’s talk on The Surprising Science of Motivation.

The role of game mechanics

If you fail to grasp the key principle of motivation, your game mechanics have no chance of being effective. But even if you do get the mechanics right, there is still no guarantee of success. To understand why, you need to understand that game mechanics are *not your core product *(unless you are building a game, of course) and have no value in and of themselves. All they can do is act as a “multiplier”, encouraging some existing behavior by increasing the behavior’s value in the eyes of the user. If that value was originally zero, game mechanics won’t help.

To put it another way, if you have a crappy product to begin with, gameplay will not save it. It doesn’t matter how many badges, progress bars, leaderboards, achievement scores, or collectibles you add, if the user doesn’t see any value in your product, you will not be successful. Moreover, the more obvious the value proposition, the less you need to bother with game dynamics. All of this is best illustrated with a few examples:

Cube Duel: a great example of well executed game mechanics—you have to play some number of “duels” before you can see your own score—but absolutely no inherent value to the product itself. Lots of people tried it for a couple minutes, got bored, and never came back.

Pandora: the exact opposite of cubeduel. From the first minute of using Pandora, its value proposition is obvious, and you’re hooked. No game mechanics whatsoever are necessary to keep users engaged.

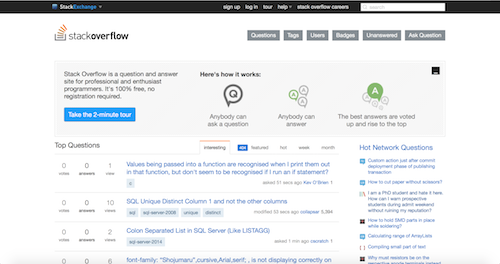

StackExchange: the StackExchange sites are a great example of a strong core value multiplied by effective game mechanics. Most users end up on one of their community sites (StackOverflow is the most popular) by googling a question. The utility of the site becomes obvious immediately: quality answers written and vetted by a community of experts. If your particular question isn’t there, you can sign up and ask. At this point, the first game mechanic is revealed: the reputation score. This score starts at zero and as it increases, various “privileges” become available: for example, you can’t add comments, create new tags, downvote answers, or offer bounties until your score reaches certain thresholds. To get your score higher, other users need to upvote your questions and answers, which encourages you to actively participate in the site. When you do this, the next game mechanic becomes apparent: your profile. Your questions, answers, reputation score, and tags from any discussions you participated in are all publicly visible. Again, the value is obvious: professional reputation. If you do a good job of participating on the site, you look better in front of employers and colleagues. Strong value * effective game mechanics = 24 million unique visitors per month (and growing).

Stop playing games. Start building awesome products.

Game mechanics can be a powerful tool, but like everything else in your

toolbox, it’s all about knowing when and how to use them. If you’re working

on some new product, start with the basics and make sure that you have the

value proposition nailed down. Only when you have something sufficiently

compelling by itself should you start thinking about adding any sort of game

mechanics.

Yevgeniy Brikman

If you enjoyed this post, you may also like my books, Hello, Startup and Terraform: Up & Running. If you need help with DevOps or infrastructure, reach out to me at Gruntwork.