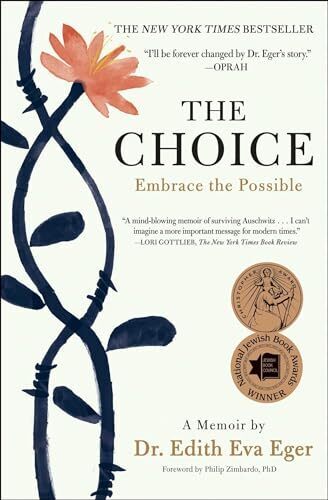

A hard, but worthwhile read. Edith Eger tells her story of surviving the holocaust, the toll it had on her life, her journey to overcoming the trauma, and how she became a psychologist who tries to help others overcome their trauma.

There are a lot of powerful, dark, haunting moments in the book. The scenes with her mother and Josef Mengele in Auschwitz will forever be seared into my mind. There’s a lot of beautiful writing too.

It’s not a preachy (like a business book or pop psychology), but it does try to leave you with a couple key lessons:

-

You can’t control what happens in life. But you can choose how you respond to it; you can choose what you notice, what you pay attention to, and what meaning you find in it. Others can take away everything else from you, but not this choice. This is a similar lesson as in Man’s Search for Meaning, which Eger says was a big influence in her life.

-

Forgiveness isn’t about the other person. When you forgive someone, that doesn’t mean that you condone their behavior or that you’re letting them off the hook. Forgiveness is about you: it’s about letting go and releasing that part of yourself that holds on to hate and vengeance and keeps you trapped. Forgiveness is about freeing yourself.

Quotes

I saved a few quotes from the book:

Tourists gather. Our tour commences. We are a small group of eight or ten. The immensity crushes. I sense it in our stillness, in the way we almost stop breathing. There is no fathoming the enormity of the horror committed in this place. I was here while the res burned, I woke and worked and slept to the stench of burning corpses, and even I can’t fathom it. The brain tries to contain the numbers, tries to take in the confounding accumulation of things that have been assembled and put on display for the visitors—the suitcases wrested from the soon to be dead, the bowls and plates and cups, the thousands upon thousands of pairs of glasses amassed in a tangle like a surreal tumbleweed. The baby clothes crocheted by loving hands for babies who never became children or women or men. The 67-foot-long glass case filled entirely with human hair. We count: 4,700 corpses cremated in each re, 75,000 Polish dead, 21,000 Gypsies, 15,000 Soviets. The numbers accrue and accrue. We can form the equation—we can do the math that describes the more than one million dead at Auschwitz. We can add that number to the rosters of the dead at the thousands of other death camps in the Europe of my youth, to the corpses dumped in ditches or rivers before they were ever sent to a death camp. But there is no equation that can adequately summarize the effect of such total loss. There is no language that can explain the systematic inhumanity of this human-made death factory. More than one million people were murdered right here where I stand. It is the world’s biggest cemetery. And in all the tens, hundreds, thousands, millions of dead, in all the possessions packed and then forcibly relinquished, in all the miles of fence and brick, another number looms. The number zero. Here in the world’s biggest cemetery, there is not one single grave. Only the empty spaces where the crematories and gas chambers, hastily destroyed by the Nazis before liberation, stood. The bare patches of ground where my parents died.

And yet. (This “and yet” opening like a door.) How easily a life can become a litany of guilt and regret, a song that keeps echoing with the same chorus, with the inability to forgive ourselves. How easily the life we didn’t live becomes the only life we prize. How easily we are seduced by the fantasy that we are in control, that we were ever in control, that the things we could or should have done or said have the power, if only we had done or said them, to cure pain, to erase suffering, to vanish loss. How easily we can cling to—worship—the choices we think we could or should have made.

Could I have saved my mother? Maybe. And I will live for all of the rest of my life with that possibility. And I can castigate myself for having made the wrong choice. That is my prerogative. Or I can accept that the more important choice is not the one I made when I was hungry and terrified, when we were surrounded by dogs and guns and uncertainty, when I was sixteen; it’s the one I make now. The choice to accept myself as I am: human, imperfect. And the choice to be responsible for my own happiness. To forgive my flaws and reclaim my innocence. To stop asking why I deserved to survive. To function as well as I can, to commit myself to serve others, to do everything in my power to honor my parents, to see to it that they did not die in vain. To do my best, in my limited capacity, so future generations don’t experience what I did. To be useful, to be used up, to survive and to thrive so I can use every moment to make the world a better place. And to finally, finally stop running from the past. To do everything possible to redeem it, and then let it go. I can make the choice that all of us can make. I can’t ever change the past. But there is a life I can save: It is mine. The one I am living right now, this precious moment.

I am ready to go. I take a stone from the ground, a little one, rough, gray, unremarkable. I squeeze the stone. In Jewish tradition, we place small stones on graves as a sign of respect for the dead, to o er mitzvah, or blessing. The stone signifies that the dead live on, in our hearts and memories. The stone in my hand is a symbol of my enduring love for my parents. And it is an emblem of the guilt and the grief I came here to face— something immense and terrifying that all the same I can hold in my hand. It is the death of my parents. It is the death of the life that was. It is what didn’t happen. And it is the birth of the life that is. Of the patience and compassion I learned here, the ability to stop judging myself, the ability to respond instead of react. It is the truth and the peace I have come here to discover, and all that I can finally put to rest and leave behind.

I leave the stone on the patch of earth where my barrack used to be, where I slept on a wooden shelf with five other girls, where I closed my eyes as “The Blue Danube” played and I danced for my life. I miss you, I say to my parents. I love you. I’ll always love you.

I walk toward the iron gate of my old prison, toward Béla waiting for me on the grass. Out of the corner of my eye I see a man in uniform pacing back and forth under the sign. He is a museum guard, not a soldier. But it is impossible, when I see him marching in his uniform, not to freeze, not to hold my breath, not to expect the shout of a gun, the blast of bullets. For a split second I am a terrified girl again, a girl who is in danger. I am the imprisoned me. But I breathe, I wait for the moment to pass. I feel for the blue American passport in my coat pocket. The guard reaches the wrought-iron sign and turns around, marching back into the prison. He must stay here. It is his duty to stay. But I can leave. I am free!

I leave Auschwitz. I skip out! I pass under the words arbeit macht frei. How cruel and mocking those words were when we realized that nothing we could do would set us free. But as I leave the barracks and the ruined crematories and the watch houses and the visitors and the museum guard behind me, as I skip under the dark iron letters toward my husband, I see the words spark with truth. Work has set me free. I survived so that I could do my work. Not the work the Nazis meant—the hard labor of sacrifice and hunger, of exhaustion and enslavement. It was the inner work. Of learning to survive and thrive, of learning to forgive myself, of helping others to do the same. And when I do this work, then I am no longer the hostage or the prisoner of anything. I am free.