A clear, comprehensive guide to the fundamentals of strength training, and how to craft routines (“programming”) that work for novice, intermediate, and advanced lifters. It’s a good mix of the science & research behind strength training, as well as practical experience in the gym. If you’re just starting with lifting, Starting Strength by the same authors is more appropriate, but as you progress, I’d strongly recommend this book too.

The only drawback to this book, and for that matter, Starting Strength, is that they tend to be optimized for athletes: that is, people whose goal is to compete in various sports (especially strength sports). That doesn’t really apply to me and many others, who instead train for general health and longevity. For these goals, I’ve found that most of what these books recommend carries over, but there are some important differences in terms of exercise selection, rep ranges, the importance of mobility and cardio, and so on. In other words, if you’re striving not to get as strong as possible, but to get strong enough, and if you’re not looking for a training plan for a competition in 6 months, but a training plan that works for decades, this book will help a lot, but you’ll want to look into other sources too.

All that said, it’s worth reading. Here are my key takeaways:

Two factors: disrupt homeostasis, recover

One of the key ideas in this book is that, in order to get stronger, your training routine must balance two factors:

- Stress your body enough to disrupt homeostasis.

- Give your body enough time to recover (which is when you actually get stronger).

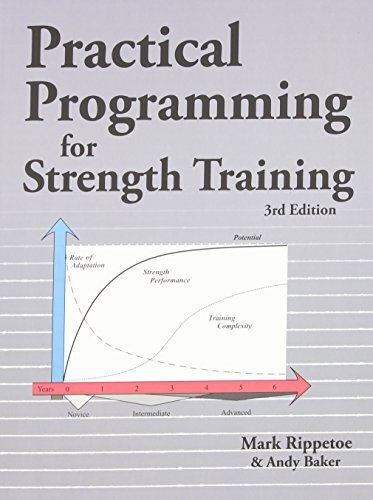

For a novice lifter, it takes relatively little stress to disrupt homeostasis (e.g., a few sets with lighter weights in a single workout), and therefore, it takes relatively little time to recover (around 48h), so they can use a routine where every other day, they can repeat roughly the same exercises, but with more weight, making progress extremely quickly.

For an intermediate lifter, it takes considerably more stress to disrupt homeostasis (e.g., more sets with heavier weights across several workouts), and therefore, they need more time to recover (around a week), so they need routines that vary exercises and volume throughout the week, making progress more slowly.

For advanced and elite lifters, training closer to their genetic potential, it takes still more stress to disrupt homeostasis (e.g., many more sets with much heavier weights across many workouts), and therefore, even more time to recover (multiple weeks), so they need routines that vary exercises and volume throughout the month, or even multiple months, making progress very slowly.

Muscle fiber types, energy systems, and adaptation

The body has different types of muscle fibers and uses different energy systems:

- Type I muscle fibers primarily rely on aerobic metabolism, which can’t generate too much force, but are highly fatigue resistant.

- Type IIa and IIb muscle fibers primarily rely on anaerobic metabolism, so they can generate much more force, but they fatigue much faster.

Training allows you to improve the function of all these muscle fiber types, but different types of training use different energy systems, and therefore, affect different muscle fiber types. For example, doing a 1RM max lift or an all-out 40 yard dash relies primarily on Type II muscle fibers, whereas doing a 1 hour run or bike ride relies primarily on Type I muscle fibers.

The key point is that you must match the training you do the training effect you want.

- If you’re looking to build strength, you need to do training that uses Type II muscle fibers, especially type IIb, which means low reps, heavy weights.

- If you’re looking to build muscle mass (hypertrophy), you need to do training that uses both types of Type II muscle fibers, which means medium reps and medium weights.

- If you’re looking to build long-term endurance, you need to do training that focuses on Type I muscle fibers, which means doing cardio such as running and biking.

Adaptation persistence

Certain types of adaptations persist for a longer time than others: for example, strength takes a long time to develop, but it also persists a long time, even if you reduce or stop training. On the other hand, cardiovascular endurance can be developed more quickly, but is also lost more quickly if you reduce or stop training.

Key insight: arrange your training to put items with longer adaptation persistence earlier and shorter adaptation persistence later (i.e., closest to the competition).

Rest and recovery

There are two types of rest and recovery to consider:

-

Rest between sets. Different energy systems and muscle fibers take different amounts of time to recovery, so the amount you rest between sets should be tied to your training goals. For example, full recovery from anaerobic exercise (e.g., weight lifting, which uses Type II muscle fibers) takes 3-7 minutes. So if your goal is strength training, you should rest roughly 3-7 minutes between heavy sets; if your goal is muscle mass, there seems to be a link between lactic acid production and increased muscle mass, so you may do better with only partial recovery, resting only 45 seconds - 1 minute between sets; and if your goal is maximizing muscular endurance, rather than strength, then you should use as little rest as possible between sets, as training your ability to recover quickly is the entire goal!

-

Rest between workouts. You don’t get stronger at the gym; you get stronger at home, as a result of recovery. Giving your body time between workouts, as well as sufficient sleep and nutrition (especially protein) is critical. However, as you get to intermediate and advanced levels, recovery times may be quite long, and if you do no training at all during those times, you may lose some degree of strength: neuromuscular efficiency is especially known to drop off quickly. Therefore, intermediate and advanced routines will typically do some degree of very high stress work (e.g., lots of volume, etc.) followed by a recovery period where you still do training to maintain neuromuscular efficiency while you recover, but at a much lower volume (so it doesn’t interfere too much with recovery).

Dynamic effort sets

Training with a high percentage of your 1RM is a great way to increase the number and efficiency of motor units recruited, so it’s a very productive way to train. However, it’s difficult to recover from. If you do it too much, especially at intermediate and advanced levels, you can develop chronic conditions such as tendinitis, ligament injuries, bursitis, etc.

Another way to increase the number and efficiency of motor units recruited is to generate force quickly and explosively. This is used in a style of training called dynamic effort, popularized by Louie Simmons in the Westside method. The idea is:

- Use 50-75% of your 1RM.

- Move the bar as fast as possible. It’s all about acceleration, which requires significant effort & focus.

- Do lots of sets, with just a few reps, and only a short rest time between sets. Example: 10 sets of 2 reps with 1 minute between sets.

Using much smaller percentages of your 1RM is a lot easier to recover from, but if you move the weight very quickly, and generate a lot of power, you still get an effective training stimulus.

Routines

The book defines a number of routines appropriate for novice, intermediate, and advanced athletes. I’ll only list a few of them here.

Note that the routines below use the terms “light,” “medium,” and “heavy.” Here is what these mean in this context:

[Novice] Starting Strength

See the book Starting Strength for details.

[Intermediate] Texas Method

- Monday: 5 sets of 5

- Wednesday: 2 light sets of 5

- Friday: 1 heavy set of 5 (alternatives: 1RM, 2RM, 3RM, or dynamic effort sets)

Monday is the “stress” workout. Wednesday is a recovery workout, mostly there to maintain neuromuscular efficiency. Friday is the “heavy” workout when the trainee has recovered enough from Monday to be able to show an increase in performance (and perhaps set a new PR). That means the weight on the bar goes up on Friday, and, assuming you complete the workout successfully, the weight also goes up the following Monday. So you’re not making progress in weight every single workout, as a novice would, but you’re making progress roughly weekly, which is appropriate for an intermediate lifter.

[Intermediate] Split Routine

Example 1 (track & field athlete):

- Monday: squat, press

- Wednesday: pull (e.g., clean, snatch) and back

- Thursday: squat, press

- Saturday: pull (e.g., deadlift)

Example 2 (powerlifter):

- Monday: bench press and related exercises

- Wednesday: heavy squat, lighter deadlift

- Thursday: bench press and related exercises

- Saturday: lighter squat, heavy deadlift

At intermediate levels, if you try to train the entire body every single workout, the workouts can get extremely long, and are hard to recover from. Therefore, the split routine is a way to train the entire body several times per week, but each individual workout is shorter and easier to recover from.