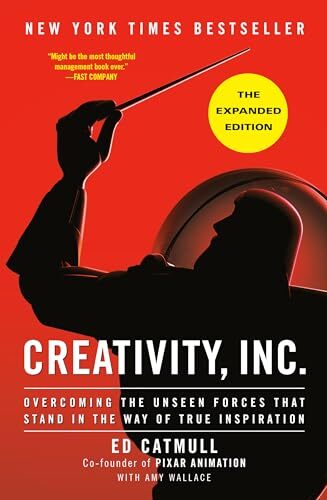

This book contains a wonderful discussion of creativity, coming up with ideas, and doing great work… Wrapped in the dull language and style of a book on management.

The book’s greatest strength is the story of Pixar itself. Its biggest weakness, ironically, is the very thing Pixar is typically so good at: storytelling. Had the book simply followed the people and process behind Pixar’s movies, showing their passion, mistakes, and struggles in a narrative style, it would’ve delivered all the same content, with none of the formal manager-speak to get in the way.

Nevertheless, the book is a must-read for anyone in a creative profession. Whether you’re a writer, artist, teacher, designer, musician, programmer, product manager, or student, the lessons in this book–many of which go counter to what you’re taught in school–are incredibly important. Here are a few of the main ones:

- Ideas are not born from a single spark of insight. They grow and evolve over a long period of time and from thousands of decisions.

- Rough drafts. All great ideas and great work goes through a very long period where it is not great. This is unavoidable, and you must protect and nurture those ideas even while they are not great, or they won’t survive long enough to become great.

- Creativity is a team sport. Real creativity comes not from a lone genius, but from a team of people willing to challenge each other and give honest, candid feedback.

- It’s OK, even necessary to attack ideas—but not people. Candor at any feedback session is essential, but it must be targeted at the work, and not the creator of that work. The creator, in turn, must realize that the feedback is meant to make the work better, and not a criticism on his or her abilities.

Quotes

Some of my favorite quotes from the book:

If you give a good idea to a mediocre team, they will screw it up. If you give a mediocre idea to a brilliant team, they will either fix it or throw it away and come up with something better.

You are not your idea, and if you identify too closely with your ideas, you will take offense when they are challenged.

Don’t wait for things to be perfect before you share them with others. Show early and show often. It’ll be pretty when we get there, but it won’t be pretty along the way.

For many people, changing course is also a sign of weakness, tantamount to admitting that you don’t know what you are doing. This strikes me as particularly bizarre—personally, I think the person who can’t change his or her mind is dangerous. Steve Jobs was known for changing his mind instantly in the light of new facts, and I don’t know anyone who thought he was weak.

Making the process better, easier, and cheaper is an important aspiration, something we continually work on—but it is not the goal. Making something great is the goal.

What interests me is the number of people who believe that they have the ability to drive the train and who think that this is the power position—that driving the train is the way to shape their companies’ futures. The truth is, it’s not. Driving the train doesn’t set its course. The real job is laying the track.

Part of our job is to protect the new from people who don’t understand that, in order for greatness to emerge, there must be phases of not-so-greatness.

In my experience, creative people discover and realize their visions over time and through dedicated, protracted struggle.

It is not the manager’s job to prevent risks. It is the manager’s job to make it safe to take them.

In Japanese Zen, that idea of not being constrained by what we already know is called “beginner’s mind.” And people practice for years to recapture and keep ahold of it.

“You can’t manage what you can’t measure” is a maxim that is taught and believed by many in both the business and education sectors. But in fact, the phrase is ridiculous—something said by people who are unaware of how much is hidden. A large portion of what we manage can’t be measured, and not realizing this has unintended consequences. The problem comes when people think that data paints a full picture, leading them to ignore what they can’t see. Here’s my approach: Measure what you can, evaluate what you measure, and appreciate that you cannot measure the vast majority of what you do. And at least every once in a while, make time to take a step back and think about what you are doing.

Many of us have a romantic idea about how creativity happens: A lone visionary conceives of a film or a product in a flash of insight. Then that visionary leads a team of people through hardship to finally deliver on that great promise. The truth is, this isn’t my experience at all. I’ve known many people I consider to be creative geniuses, and not just at Pixar and Disney, yet I can’t remember a single one who could articulate exactly what this vision was that they were striving for when they started.

In my experience, creative people discover and realize their visions over time and through dedicated, protracted struggle. In that way, creativity is more like a marathon than a sprint. You have to pace yourself.

Too many of us think of ideas as being singular, as if they float in the ether, fully formed and independent of the people who wrestle with them. Ideas, though, are not singular. They are forged through tens of thousands of decisions, often made by dozens of people. To reiterate, it is the focus on people—their work habits, their talents, their values—that is absolutely central to any creative venture.